Wearing the Wayback Machine

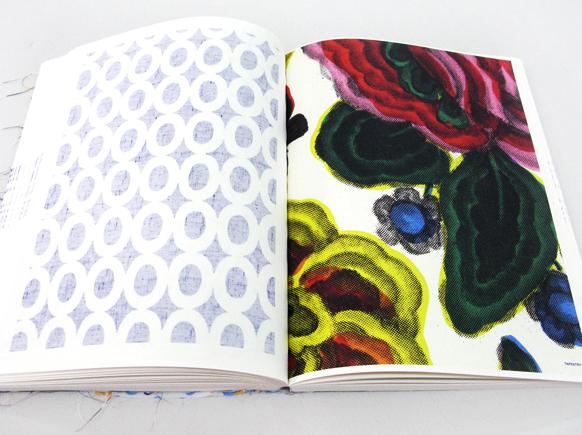

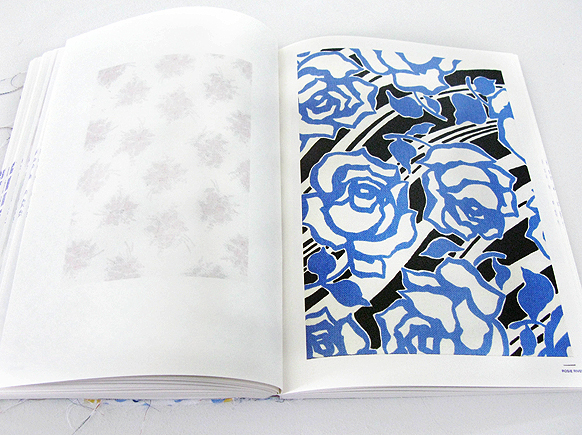

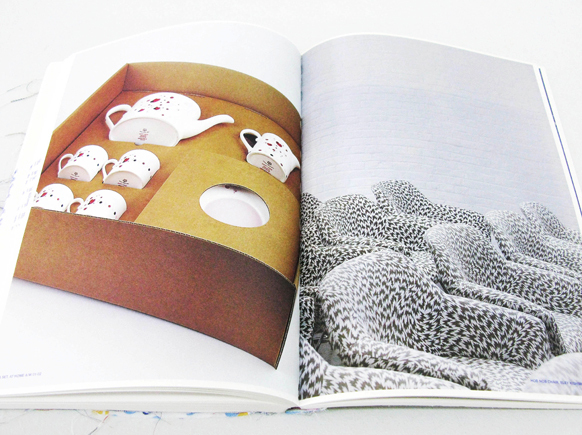

The archive of husband-and-wife design team Eley Kishimoto is, to put it mildly, extensive. For two decades, Mark Eley (from Brignend, Wales) and Wakako Kishimoto (from Sapporo, Japan) have launched an ocean of pattern from their south London headquarters. Whether designing women’s fashion, wallpaper or crockery, these days their name is synonymous with masterful surface design.

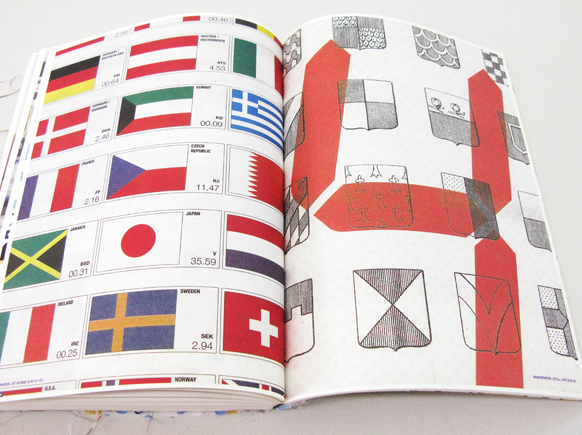

Paris, London and Tokyo are home to their most fervent fans. (The French artist Sophie Calle, who says she dresses in nothing else, helped launch the duo onto Paris catwalks in 2008, as joint Creative Directors of Cacharel). But their own Eley Kishimoto women’s fashions, begun in London during 1992, are worn round the world by pop stars, socialites – even cartoon characters.

Despite its success, EK’s founders are not confined by fashion. In fact, they are eager to leap on any challenge that involves pattern. Their company’s bold and rhythmic prints attract different kinds of clients – from Joe Casely-Hayford and Hussein Chalayan to Yves Saint-Laurent and Louis Vuitton, Sonja Nuttall and Marc Jacobs to Warp Records and Joop!. Yet the pair has also designed sneakers, beer cans and a Volkswagen, dressed artist Éric Duyckaerts to represent Belgium at the Venice Biennale, worked with Lewis Leathers and made furniture for Habitat.

”We’ve believed in collaboration since the very beginning,” says Eley. “At first working with others gave us a way to survive and still communicate. Now we see it as the most creative way to experiment.”

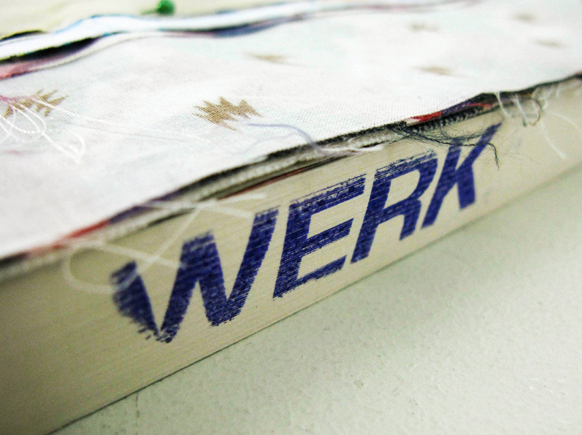

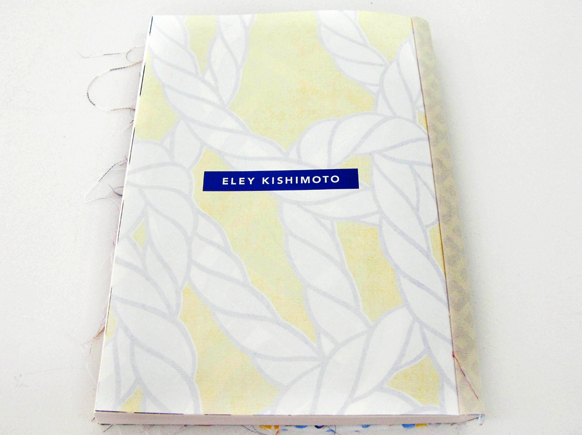

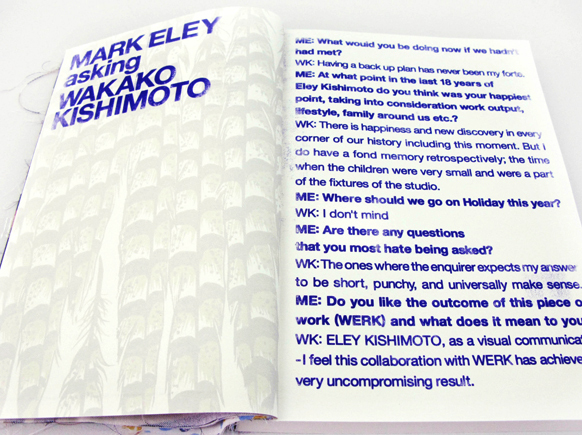

The duo treasures that archive they’ve built over twenty years. They even let design star Theseus Chan produce a volume of his WERK series in homage to it. Eley says they seduced over by Chan’s “sophisticated simplicity” and the singularity of WERK.

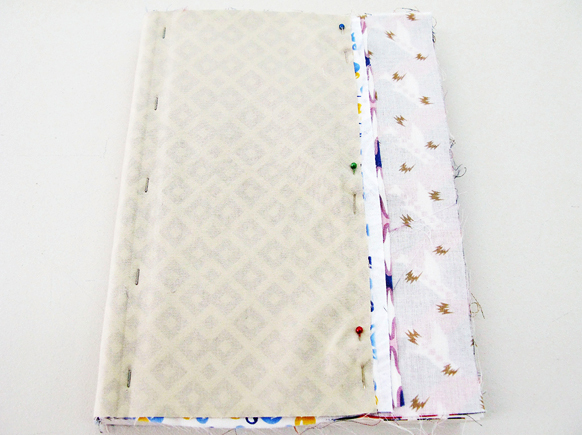

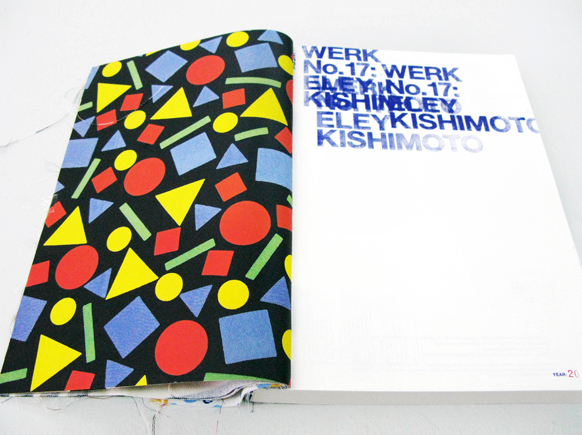

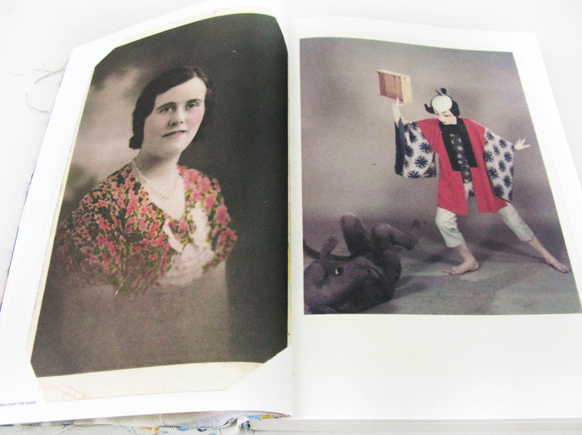

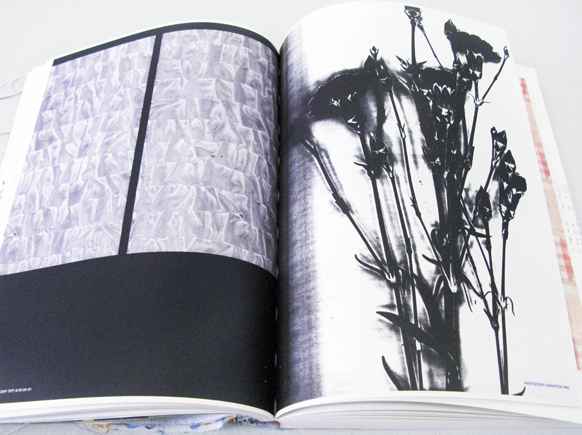

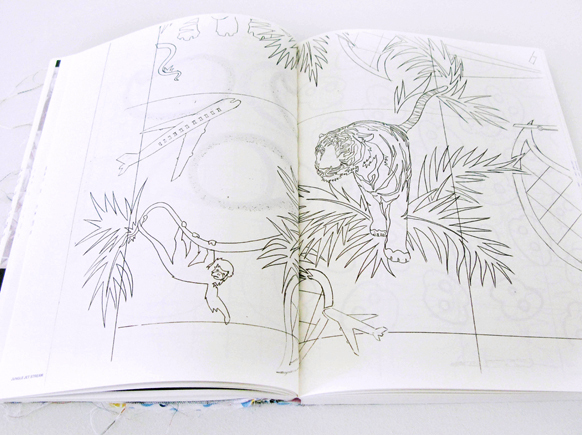

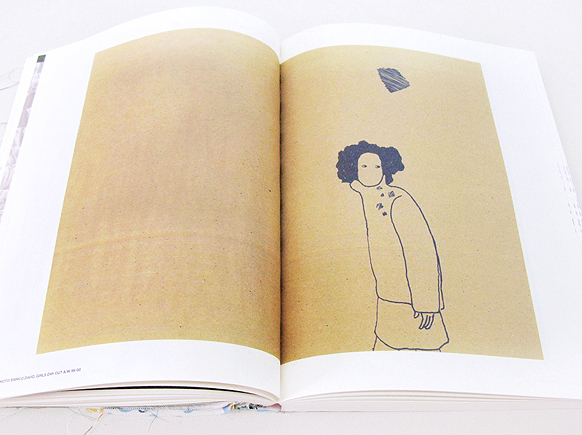

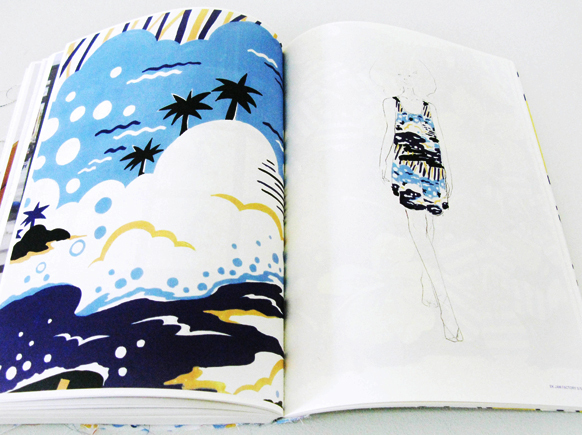

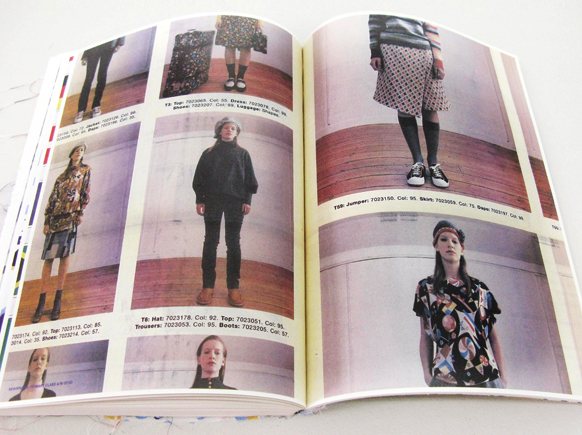

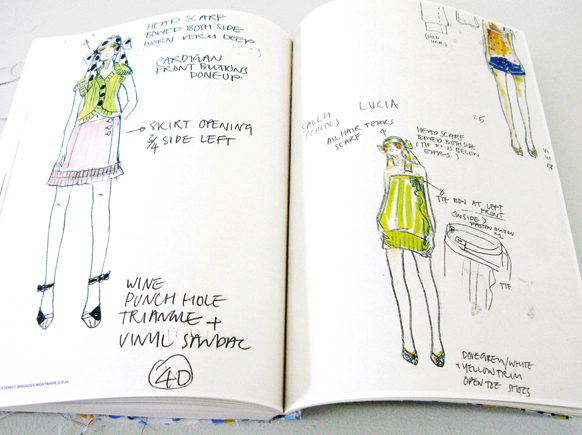

Every edition of these artists’ books features a separate talent; each and every volume is literally hand-finished. EK appears in WERK 17, which includes actual fabrics, as well as sketches, photographs and other memorabilia. It appeared between “issues” about the illustrator-filmmaker Joe Magee and the psychedelic designer Keiichi Tanaami. “Collaborating with such artists”, says Chan, “often happens by chance.”. He says he first encountered Mark and Wakako in Singapore, through a design professor who works in Glasgow.

At the same time, WERK was delving into EK’s archive, Eley and Kishimoto started EK Jam Factory. An enterprise named for the original function of their studio, this is a fashion label being developed with partners like America’s Anthropologie and Scandinavia’s Weekday. Says Eley, “It’s the archive which made that possible; using it, we create items tailored to different clients, make pieces out of season and price them more affordably.”

The couple also used their history at 2010’s London Fashion Week. There they held a special event called Flash On Week. It celebrated the versatility of their pattern “Flash” which was created in 2001. Everything on show was covered in the motif but all were different projects for different companies: beach shorts for Orlebar Brown; iPad and iPhone cases for Incase; beer glasses for DUVEL; a leather journal for Noble Macmillan.

For bicycle czars Cinelli, EK had Death Spray Custom apply Flash to a Supercorsa, then designed a set of cycling gear to match. For BMW France – a company which has patronised the arts since 1975, when Alexander Calder created an “art car” for them – EK customised a BMW R 1200 R motorbike.

The Flash pattern, says Eley, proves the archive’s timelessness. “We took something out of the fashion cycle for which it was designed just to see if it could achieve longevity. First we did wallpaper with it; after that, some Converse sneakers. Since then, that pattern has developed a kind of viral identity.” Flash can now be found on T-shirts, acrylic nails, a skateboard, the Eastpak backpack and Medicom’s cult Japanese be@rbrick teddies.

Flash may have a different relationship to the archive than that of WERK or Jam Factory clothes. Yet all help place Eley Kishimoto in context: a streamlined modern version of the English Arts and Crafts movement. While Theseus Chan feels “there’s just too much ‘design’ out there”, Eley says his company sees it as the world “getting smaller”.

”To be aware of the global creative system and the output of its schools, I find all that very interesting. I’m always searching for inspiration and motivation. So I think, ‘I might possibly find it there’. I know we’ve come a long way and I’m proud of our archive. Nevertheless, we are just a component of one moment in history.

Predecessors like the Arts and Crafts movement – and all such groups of applied artists around the globe – we respect their work so much. If there is any chance for us to be remembered the same way, we would be privileged.”