Meeting Monique, obliquely

The installation “Rachel, Monique” by artist Sophie Calle deals with the death of her mother, after whom it is named. Her struggle to wrench something positive out of this loss drives the production.

Opening just after Toussaint, that annual moment which honours the departed, Calle’s installation is everything but traditional. This may be what one has come to expect from the artist. But here, even for her, both circumstance and subject are singular. Add to this that her tribute has been staged in the vast underbelly (currently being demolished) of the Palais de Tokyo. A visitor must descend into this incredible landscape, where Calle says she has tried “to hide myself all over the place”.

Humour is surprisingly central to the piece; it gives the homage extra punch and ends up subtracting nothing. Monique, we learn, regretted she had never appeared in her daughter’s work. But during what would be the last hours of her life, this changed – to her mother’s satisfaction, Calle relates. “When I posed my camera at the foot of the bed in which she agonized, because I feared she would pass away in my absence, because I wanted to be there, to hear her last word, she exclaimed to me, At last!”

A pilgrimage from spot to spot throughout a giant space, the work is held together by the ties between mother and daughter. Putatively exposed from the start, their subtlety and depth are discreetly revealed as one completes the promenade which seems, in fact, as if one were visiting many graves. Rather than one concerted grief, it feels like a family of losses, surprisingly able to speak to anyone.

This achievement, we learn, was predicted by Calle’s psychic. At the time, as an art project, she was sending the artist on a series of arbitrary journeys. (Calle was meant to obey without objection). These included a pilgrimage to Lourdes at the very low point of the grotto’s “season”. In view of her mother’s accelerating decline, Calle says she undertook the trip reluctantly. Her psychic, however, insisted it would produce something: “a fashion of enlarging your grief, of raising your personal history to a collective level”. Whether or not the Virgin did help her communicate, Calle notes she did learn one fact. No first-time pilgrim to Lourdes should never tutoyer (speak in the familiar tense with) the Mother of God.

Forged from idiosyncrasies, the installation nevertheless functions as predicted. Monique, we learn, longed to visit New York once more (it was too far away) and wished she could have fulfilled her dream of seeing the North Pole once. (She had to settle for a pedicure and a trip to the seaside).Yet after her mother’s passing, Calle herself sailed to the Pole, bringing Monique along in the form of her diamond ring, Chanel necklace and photo. These she interred in a glacier, wondering if global warning would melt it and send Monique on another voyage – or if future explorers might discover the ring and use it to argue the greatness of Inuit craftsmanship.

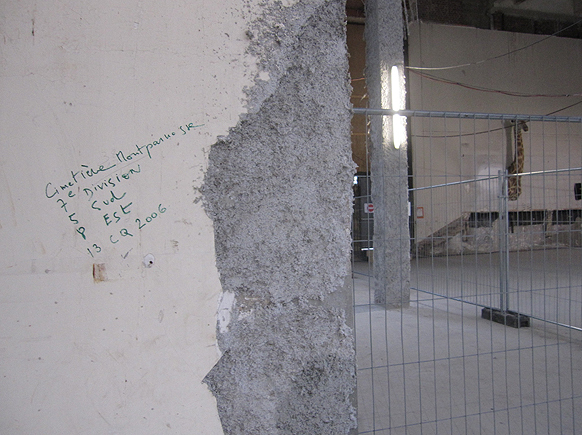

Traces of Monique are scattered like ashes. We learn she chose a piece of music she hoped to die while listening to (Mozart’s concerto for clarinet in A major, K. 622). She carefully decided her “final address” in the Montparnasse cemetery (Calle scrawls it on the wall next to a photo of her gravestone. Her last words were “don’t you worry” (yet repetitions of the word worry, souci, are everywhere). The epitaph Monique chose for herself was_ Je m’ennuie déjà_ (‘I’m bored already’).

The last view as such comes just after one enters. A row of photos of other graves, each one marked “Mother”, are set flat on the floor, like calm pools of water. They lead to a photograph of Monique in her coffin, her shroud almost covered by carefully chosen objects. Present are the shoes and the dress she had chosen for burial, some of her favourite candies, stuffed cows she had collected, copies of Proust and Spinoza, a postcard of Marilyn Monroe.

Yet everything in the exposition really centers on a small shack, made out of rough wood and positioned off-center. Here screens the 20-minute film Calle shot at her mother’s bedside, which records the final moments of her life. It’s hard to say what one sees viewing it; is there breathing, is there a sigh? Did that eyelid flutter? Even those around her search for signs of life or death, feeling for a pulse, reaching to see if a breath was expelled.

Neither grim or voyeuristic, neither poetic or pretentious, this is one of Calle’s simplest-ever presentations. As a final gesture of love, it is both honest and modest. Death, Calle has to admit, is literally “unknowable”. One moves on to her final tableau, in which the gravestone marked “Mother” is far away. Only its tribute, her vase of lilies, remains alive and nearby.