Art at home with heroes

The monumental installation Leviathan Thot, by Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto, typifies the epic public art that makes Paris unique. As part of the Paris Festival of Autumn, it ran from 15 September to 31 December 2006. It marked the beginning of an ongoing relationship between the artist and French art-lovers.

The work was named after two opposing forces. One is Leviathan, the Book of Job’s destructive monster. The other is ancient Egyptian god Thoth, the inventor of writing and scholarship.

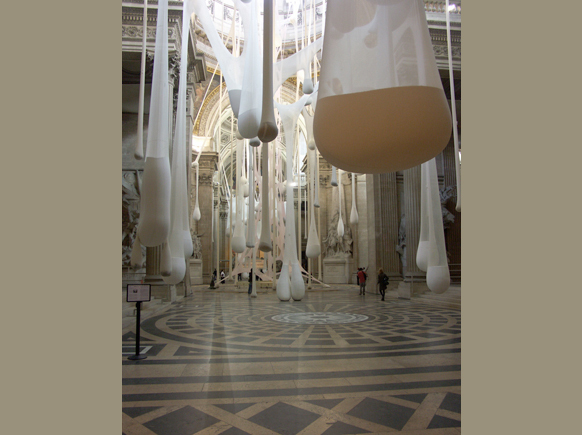

Its venue, the Panthéon, is the hallowed place of final rest for great French heroes. Those interred here range from Voltaire and Rousseau to Louis Braille and Marie Curie. Others whose bodies were lost but who are commemorated include résistant Jean Moulin and author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

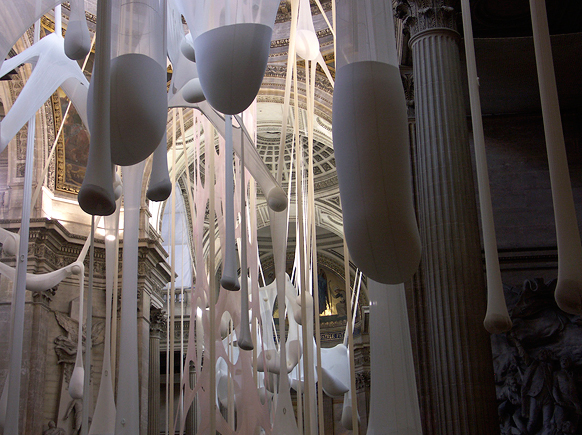

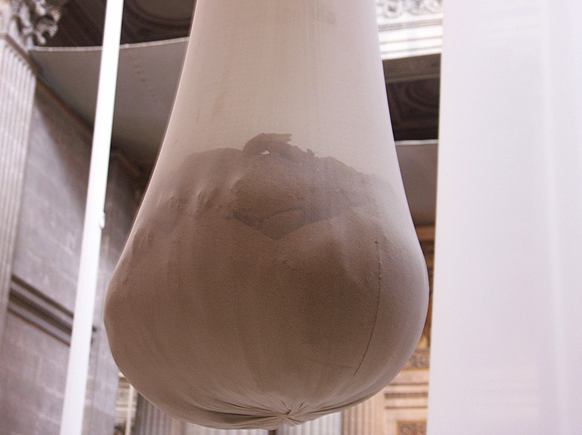

The “creature” designed by Neto to inhabit this vast space was fabricated out of his trademark nylon tulle. Stretchy and semi-transparent (the same material is used to make women’s hosiery), the artist has pioneered its use in creating ingenious structures. Their complex hanging forms are always weighted with natural materials; these can be stones, sand, spices or rice. At the Panthéon, he added dirt and pellets of polysterene.

Neto was born in 1964 in Rio Janeiro, a place whose culture helps shape all of his work. He describes it using terms like “slowness” or “sensuality”, and says it greatly sharpened his sense of the clashes between nature and culture. In Rio, Neto notes, nature is lush, often melodramatic – and ubiquitous. “This is a city surrounded by mountains, one confronting the sea, lakes and the bay, one with rich rainforests…It gives one the revelation that civilisation has its limits. The city is always trying to grow, yet the river constrains it.”

Neto always seeks to immerse his viewers completely. The energy that drives all his work, he notes, is gravity. “Its form and its contours are only defined once the material is stretched inside a space. There is always tension, just as there are tensions between nature and society.”

This artist saw the Panthéon as a perfect setting in which to visualize the basic conflicts that fascinate him. After all, its history embraces rationality, Revolution and Occupation. “In this work, you have the body and its ‘harness’: society. It can’t be seen outside the context of this historic building because the Panthéon acts as its cocoon.”

The breathtaking “Leviathan” proved more than the equal of its stately home. In gratitude, la France made Neto un chevalier de L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. The French had taken the artist to their hearts with many critics noting how, as a university student, gave up electrical engineering to study art – and astronomy. In 2007, Neto was given a residency at l’Atelier Calder and in 2008 he presented a site-specific work for Maison André Bloc, the extraordinary home of the late architect. Made of logs that were used like Legos, it offered a vivid evocation of the rainforest.

Almost always, works by Ernesto Neto are huge. But both earlier and later works have been been more playful. At the 2001 Venice Biennale, he filled a ninth-century warehouse with his homage to Marco Polo, weighting and colouring its pendulous pieces with spices. In 2010, for London’s Brazil Festival, Neto’s The Edges of the World drew media attention even from CNN.

The engineering feats involved in mounting “Leviathan Thot” were available for viewing in the Panthéon. But, as its curator of Neto’s equally complex work for the Hayward notes, “No matter how beguiling and immersive it seems, his work is always sculptural.” Indeed – its artistic rigour was qualified for that place in the Panthéon.