Wright on target

The talents of Londoner Ian Wright fit his city perfectly; his curiosity has kept pace with it over decades. “For me, London’s all about the people and the place, even though it’s changing more rapidly than ever. Every time I leave and return, I can look with different eyes. Right now, I think there’s this great kind of creative explosion.”

Yet Wright knows his home is becoming homogenised. “It’s like we were waiting all our lives, thinking, ‘It would be so great if we could just have cool clothes, have really good sounds, have our little place to go.’ Then we got it all at once… but so did everybody! You start to think, ‘Hey maybe that really wasn’t what I wanted. I mean, maybe I wanted all that but I wanted to work for it.”

Wright’s love of London has always been centred by work. His business card used to read ‘Painter and Decorator’. The joke stands today, because fancier terms still short-change his inventiveness. One moment Wright is re-drawing Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen with pushpins, the next he is ‘painting’ rapper T.I. using shredded paper.

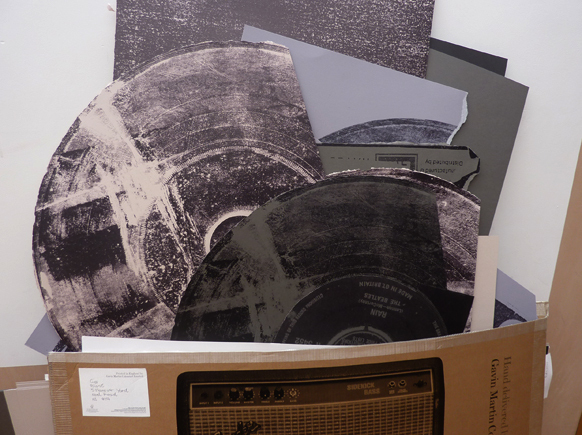

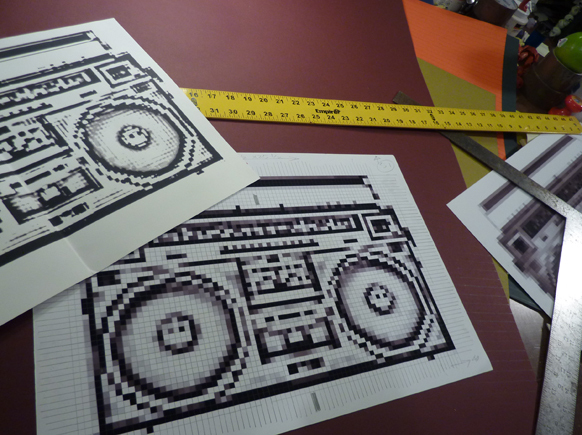

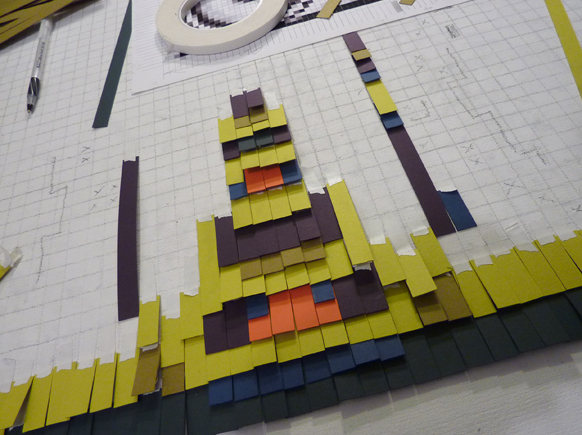

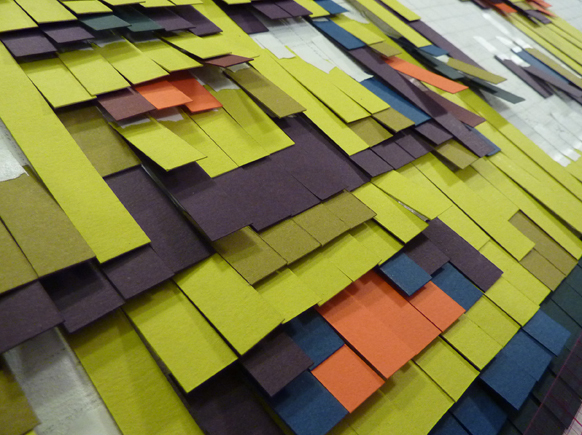

He also likes to push his mechanical tools in strange directions. Three decades back, Wright was using a Xerox copy machine to parody screen-printing. Now, while eager to avail himself of the latest software, he imitates the universe of pixels with Post-Its or carpet tiles. It is a mix of warmth and disrespect that, over the years, has yielded stunning accomplishments.

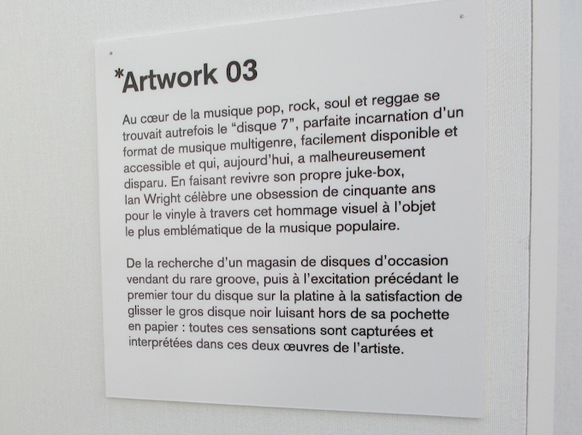

Wright’s deepest passions – music and making – have also made him into something of a nomad. He spends a lot of time in New York, where he is represented by Christopher Henry Gallery. Yet he also keeps his cluttered desk in a shared north London studio. Wherever he makes it, Wright’s work travels even further. Recently, it has been featured in Hong Kong (at the Agnès B librairie galerie and the Wan Chai Centre), in the Czech Republic (at the 22nd Biennale of Graphic Design) and in Chaumont, Switzerland (at last year’s Graphic Design Festival). In 2010, he was the subject of a French monograph, ian wright, by Pyramyd. This year, a trio of his commissions helped open the Foire internationale d’art contemporain in Paris.

Over a steaming cup of tea in Arthur’s café (E8), Wright discussed his unorthodox methods – a chat he later completed in a tabac on the rue de Fleurus. Both conversations focused on a central question: why does he always see his subjects in such strange materials?

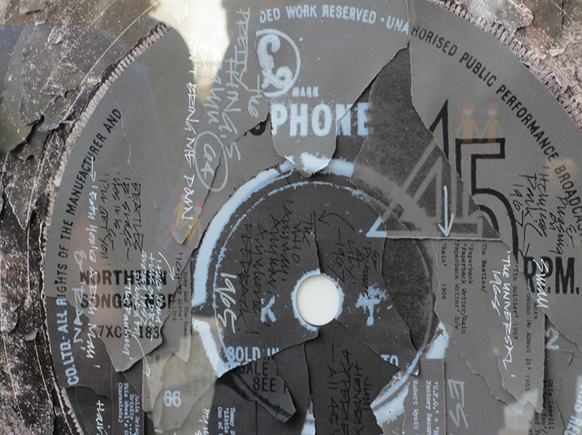

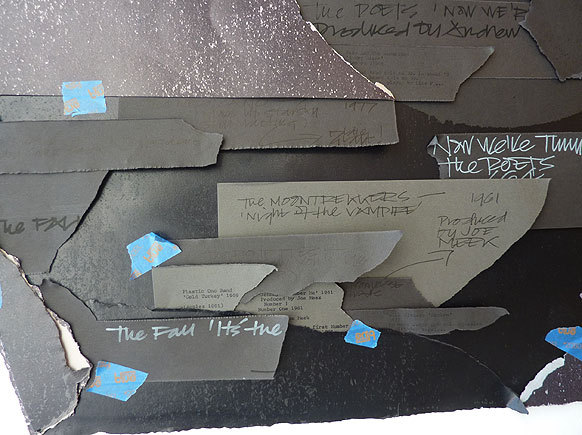

”I think that only makes sense to me now, because I never thought about it as I went along. Even at New Musical Express, when I did a portrait a week, each one was just trying to evoke a feeling. Whether I ended up making it out of cassette tape or on a breadboard, the materials were a way of putting across what I felt. It was always about the subject and their sound, that certain person.”

”I studied graphic design and, when I left college, I was surrounded by some of the best drawing talent in London. That made me look for a different way to express myself. I had also struggled with drawing and painting. So I used to try and process things a little more. Try to make them have more soul. Because salt or ripped-up papers still aren’t paint, I wasn’t scared of them. They just seemed more throwaway. For me, there were rules with paint. Which, of course, came down to my ideas of what paint was ‘about’.”

”It also took a long time for me to understand that formal work just wasn’t what I wanted. I liked to play and I couldn’t play enough. I taught for years and, if I’d been teaching then, I would have told myself, ‘Look, don’t be ridiculous!’ But, instead, it was like: if I can use different materials they will make me different – and maybe I can do it in a way that will keep me interested.”

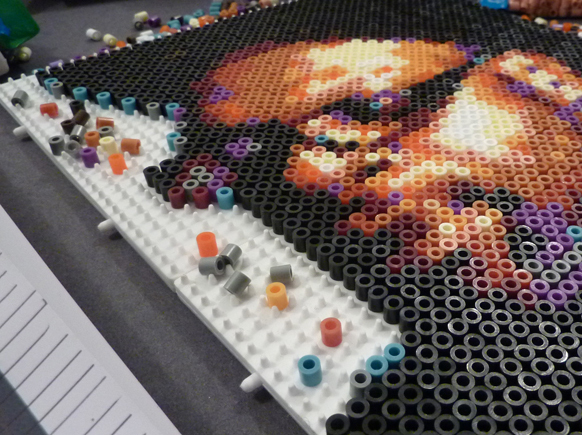

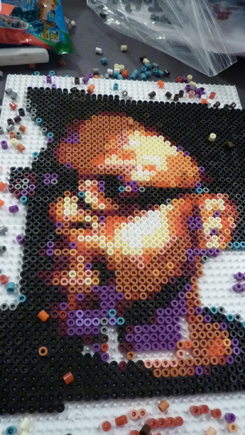

”Really I’m always trying to escape print and the static page. When I first started making images out of things, for instance, I began with these little beaded heads. I wanted to figure out how to apply kids’ toys to something bigger. Just how could I use paper cups or whatever? That grew into this different way of working and I like to think I got there pretty organically. It wasn’t planned and it’s not at all about deconstructing anything. It’s still trying to build an image of how I see the thing.”

”Also it’s ephemeral, like an installation or a performance. Okay, it might be printed or recorded or photographed. But it doesn’t need to be lasting. It might sound kind of funny for me to say that, because I do like to re-investigate things. I mean, every couple of years, I do a portrait of Jimi Hendrix. There’s just something about him – it’s not about his music or even how he looks. It’s more about how, in old photos, he’s in colour when the world was still black and white. There’s something fluid about him, something very sonic.”

”I like to find new ways to look at that. Like I used his image again for this Colourful Life project. The guys behind that make these papers I’ve been using since I started. So I made his image out of little rolled-up cones of those. That provided this nice play of light; it brought the piece some depth. Plus the cones were like flowers, so the image could sort of bloom.”

”Choosing something visceral like that becomes experimental. It’s a bit like when I first tiled a kitchen, I did a few rows but then I had to stop and refine it. Of course I was scared because there are all these blokes who lay tiles for a living. But, then, there’s bluffing in everything. Often you’ll have no real idea how some thing is done.”

”Nowadays, there seems to be more promotion attached to everything. Our field of making images, it’s inching close to acting. Because people look at your work and they make assumptions about you, about what you think and what you can do or not do. They’ll typecast you. Also, our anonymity creates this pressure for personal relevance. Because it all seems so transitory, you have to keep it relevant. That’s become a big part of carrying on in the world.”

”You could argue for ideas, that you have to be saying something. But it’s more like things change around you and they’re changing faster. Or maybe not changing faster but there’s more to look at. Print, film, DVDs, digital film, the Internet…There’s now so much stuff that’s always vying for your attention. You have to both nail something and rise beyond the moment. In my opinion, there always has to be something there.”