Warhol of the Victorian Age

The objects called carte-de-visites created the biggest collectible craze of Victorian Europe. These tiny cards (named after the visiting cards they resembled) were photographs pasted onto stiff cardboard. It was a French photographer, Louis Dodéro, who first enhanced visiting cards with portraits. It was another, André Adolph Eugéne Disdéri, who created the technique that their manufacture feasible.

Exposing small images in multiples on one negative allowed several poses at once. Unlike a dauguerrotype, this used a collodion process – which was cheaper and made sittings quicker. The portraits it produced were also more natural and life-like. Combined with mass-manufacturing, this turned them into a Paris fashion.

The French fad soon consumed all of Europe. For the first time, ordinary people saw what their rulers or favourite singers looked like and, more excitingly, they could afford to possess such images. In 1859, Napoleon III invited Disdéri to shoot his portrait. So many royals and socialites imitated him that, by April 1860, Le Monde dubbed Disdéri’s salon “the Louvre of the carte-de-visite”.

Yet London played its own role in the craze. Like Worth the fashion designer, Disdéri opened a secondary maison here. But the medium’s Warhol (yet another Frenchman) was an expatriate who chose to work in England.

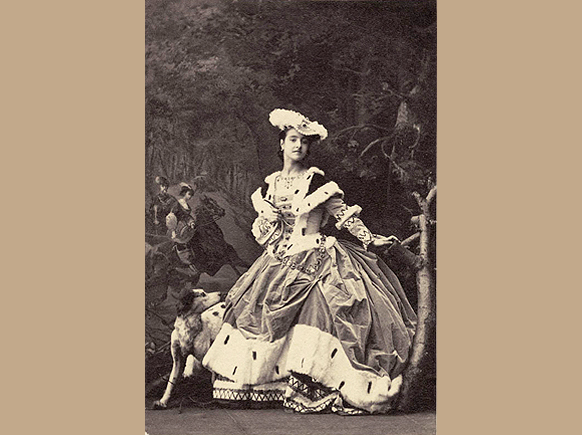

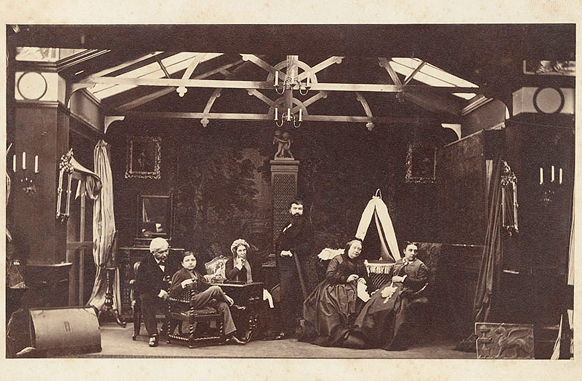

Camille Silvy studied photography in France. But he was clever enough to launch himself in a new arena. In 1859, he bought a London photography business. Enlarging its imposing premises, he added deliberate touches of Parisian grandeur: assisants, well-stocked dressing rooms, sets, props and wardrobes. His sitters were treated like royals, with Silvy donning white gloves before ever touching them.

Trappings were important because Silvy made his portraiture pay. At a time when Dickens paid magazine staffers five guineas a week, a single Silvy ‘sitting’ cost three guineas. Nevertheless, subjects were guaranteed to look à la mode. Silvy dressed his wife in the latest Paris fashion and he encouraged clients to do likewise. His cartes are prototypes of early fashion photography.

Silvy had one stroke of luck that ‘made’ him early on. In addition to commercial work, he was always experimenting with art photography. When a French neighbour showed four of these photos to Queen Victoria, both she and Prince Albert pronounced them magical.

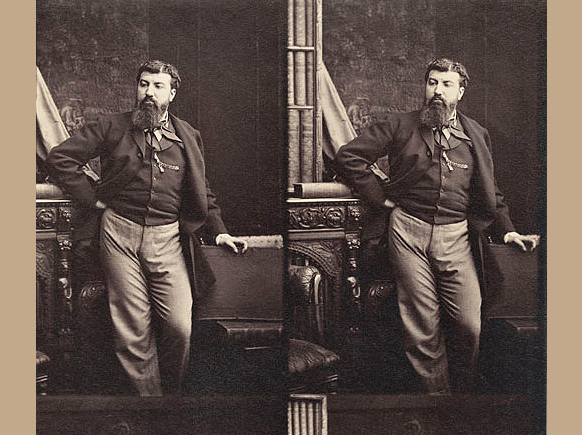

The Queen became a fan, sending friends and family to Silvy’s studio. A single “Daybook” from his firm, C. Silvy & Co, records a list of well-born sitters: the Queen’s Lord Chamberlain, three Dukes, eight Duchesses, three Counts, twenty-three Countesses, three Marquises, eight Marchionesses, ten Viscounts, thirty-two Lords and “more than one hundred” Ladies.

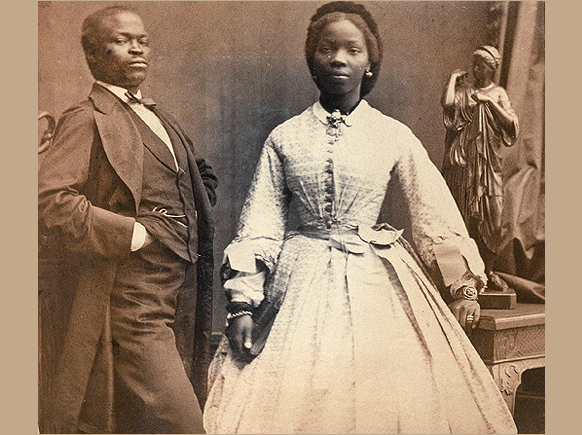

The expatriate also wooed stars such as famous actors, comedians and opera singers. His atelier ran its own production facility, supplying carte-ready portraits to Regent Street’s Marion & Company, the top wholesaler of the genre. With celebrities, Silvy’s business savvy often appealed. Through him, they could popularize their faces, publicise projects and even gain a slice of the earnings.

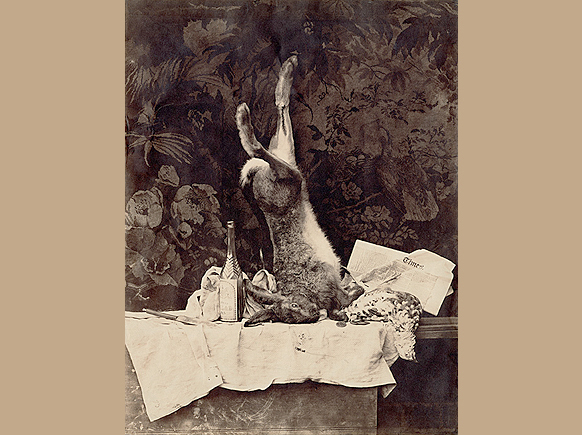

Silvy was a genuine pioneer of photography. To capture Members of Parliament at work in Westminster Palace, he created a mobile studio. He also capitalised on cartes as wedding souvenirs, experimented with hand-tinting them, even produced (with help from France) versions in photo-enamel. He even tried creating an early Google Books, whose photographed facsimiles rendered faded ink in ancient works more legible.

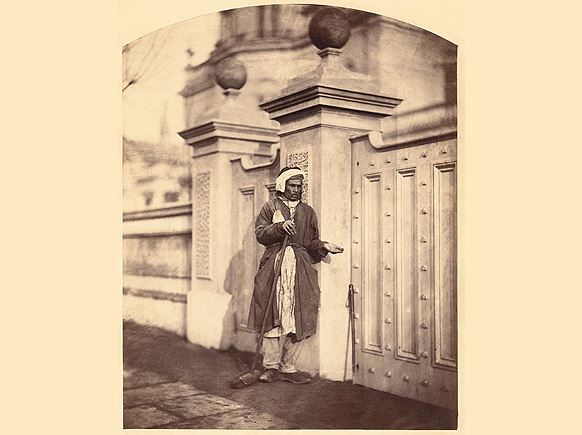

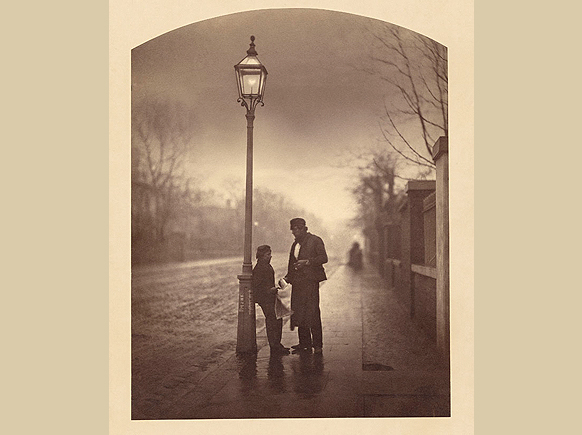

Dickens, Silvy’s contemporary, was one of his inspirations. Like him, Silvy relished making moving portraits of children. The lensman also captured those ordinary Londoners who fascinated Mayhew and Dickens: immigrants, street sweepers, manual workers and corner musicians. When Silvy launched his own photo publication (simultaneously in London and Paris), he often mentioned Dickens as a possible partner.

His work anticipated that of Andy Warhol. Not only did Silvy break new ground in the ways he enshrined celebrities. He also evolved techniques, such as composites made from separate negatives, that let him manipulate images and compositions. Like Warhol, Silvy saw his medium quite pragmatically: to him, it was both artistic and commercial.

At the height of his fame, the photographer shot a different sitter every twelve minutes. At that point, Silvy likened his logo (which was based on his signature) to “legal tender, like a note from the Bank of England”. He was also proud of the special packaging – boxes with his own “crest” – which was used to package cartes from his studio.

The cartes craze had diminished by 1867. So Silvy took yet another of his ideas back to Paris. Sensing that war between France and Prussia was imminent, he created a “panoramic method” for shooting battlefields. A long spell of ill-health from fog and coal pollution ended with his announcement he was closing his London studio. When war finally broke out in 1870, Silvy fought for France as he did everything else – with energy.

A decorated war hero, he began to write his memoirs. But they were halted, in mid-stream, by illness. After years of alternating between manic work and exhaustion, Silvy was diagnosed with folie raisonnante. It was the end of his singular career, one remembered by the greats of his time (such as Félix Nadar), then forgotten by later critics. Silvy spent his last thirty-one years of life in care, dying of pneumonia in 1878.

A landmark 2010 exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery finally positioned him as one of the first creators of modern celebrity.