Reinventing French recreation

He is famous for elegiac portraits of elegance. But Jean Antoine Watteau was not a typical high-society painter. Preceded by the heaviness of royal Baroque, followed by imitators who wallowed in the luxuries he depicted, his own works show a different type of radical talent.

By reuniting Watteau’s key drawings, London’s Royal Academy showed how and why they engineered changes in taste. Perhaps only an outsider like Watteau could have managed it.

The son of a provincial tile-maker of Flemish heritage, Watteau started painting around the age of ten. At 18, he came to Paris. Poor and alone, historians think he worked as a fashion engraver or a set designer. Certainly, he found both friends and employment in the theatre. Watteau worked in the studio of Claude Audran III, the decorator of royal homes and curator at the Palais de Luxembourg.

But he also painted souvenirs near Notre-Dame. The one thing he never actually formally studied was art. In a complete difference to his fellow artists, few of the drawings he left were made in preparation for paintings.

Watteau drew because he loved to draw. Sketching constantly, with application and curiosity, was the way he came to understand the world around him. Although he developed great expertise in depicting them, Watteau also looked beneath social frivolities. This was partly a result of his personal isolation.

Sickly and tubercular, the artist died at 37 – always having lived alone or with friends. Even as he struggled with his failing health, his savings vanished with the crash of the French Royal Bank.

Although concerned with public life and its rituals, Watteau’s art is actually intriguingly private. What it truly concentrates on is the moment. This the artist seizes with a stunning virtuosity and a gaze so penetrating the human beings it serves up still seem to be breathing. His restless eye explored an unconventional range of subjects, from visiting Persians to weary working soldiers.

Watteau focused not just on those in satin, but also on the poor who came to Paris, as he had, for a better life. Some of his sketches juxtapose porcelain beauties with exquisite studies of their young black servants.

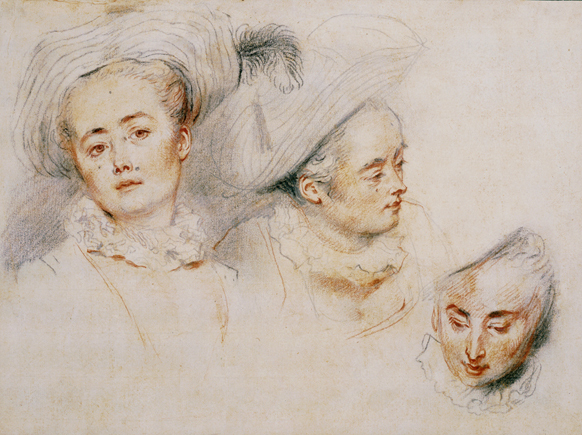

His first drawings were made using warm red chalk but he soon added black and white to capture light, depth and form. With this technique, known as aux trois crayons, he produced page after page of energetic studies. Although these were executed two hundred years ago, each still exudes warmth and presence. Theirs is an intimacy that speaks directly to viewers.

In a show curated by Pierre Rosenberg (Président-Directeur of the Musée du Louvre) and Louis-Antoine Prat (Chargé de mission in the Louvre’s Département des Arts graphiques), visitors got a one-time-only chance to compare works normally scattered in private collections – or seen in splendid isolation at sites such as the Louvre and British Museum.

Often their pleasing lines appear almost musical, for Watteau clearly had a genuine love of music. His drawings of those playing and listening (rapt, transported faces or even disembodied hands) offer uncanny portraits of the way it can heighten emotions. Equally, the play of light he orchestrates on fine fabrics, on children’s skin or on various elements of his landscapes, provides a startling anticipation of the Impressionists.

Watteau is the inventor of la fête galante, a genre that shows the bourgeoisie at play outdoors. It was an update of the classic format which portrayed mythical beings in pastoral settings. At first, the formula flummoxed French art authorities. Yet these very academics were one of the new style’s targets. For, rather than selling to royals or aristocrats, Watteau’s art was purchased by rich bankers and tradesmen. But this did not stop their author from craving that formal acceptance available only from the Académie des Beaux-arts.

His solution was to forge a style they could accept. He replaced traditional nymphs and shepherds with posh Parisians – shown at play not in some mythic Arcardia, but in their own contemporary parks and gardens. He personalised the scenes with figures from two ‘outside’ worlds, those of the theatre and of music. Many of the models for such protagonists were Watteau’s own friends: Parisian actors and musicians he often drew.

As a special counterpoint to the RA show, the Wallace Collection re-hung their Watteau holdings. In the lavish splendours that comprise Hertford House, the fête galantes appeared much as contemporaries would have seen them. The concurrent shows emphasised Watteau’s singularity. For the artist populated his work like a casting director, with all its players and extras plucked out of his countless sketchbooks.

His informality is shaped by a decisive touch. It was in painting with this certainty, outside tradition, that Watteau altered the course of French art. Without him, Fragonard would not have conceived “The Swing”, nor Manet Le déjeuner sur l’herbe. Via his opportunistic patron Jean de Jullienne (centrepiece of a second show at the Wallace Collection), Watteau became the subject of serial posthumous catalogues – many issued as long as fifteen years after his death. The first one, which contained engravings of the artist’s drawings, gave a teenage François Boucher work as a copyist.

These helped solidify Watteau’s continued influence, even in fields such as fashion and décor. He drew the robe à la française, for instance, so perfectly that its trademark ‘sack-back’ is now called les plis à Watteau. As the French Rococo style fully flowered, de Jullienne’s catalogues became reference books for artists, decorators and workers in the world of la mode.

Much more fascinating than his legend, however, remains the artist’s inscrutablity. Always at one remove from his presentations, Watteau was one theatre-lover who saw all life as a stage. His very informality had choreography; even when filled with assorted heads, hands and profiles; every drawing demonstrates a perfect sense of balance. The pleasure Watteau took in this comes across, as does a powerful sense of melancholic empathy.

His drawing ability remains spectacular. But even more startling is his modernity.