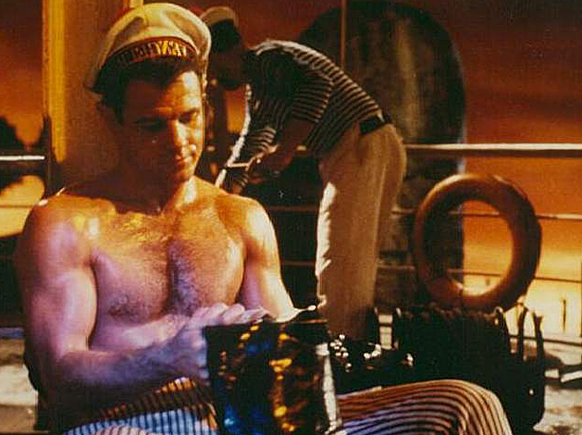

Hello sailor...

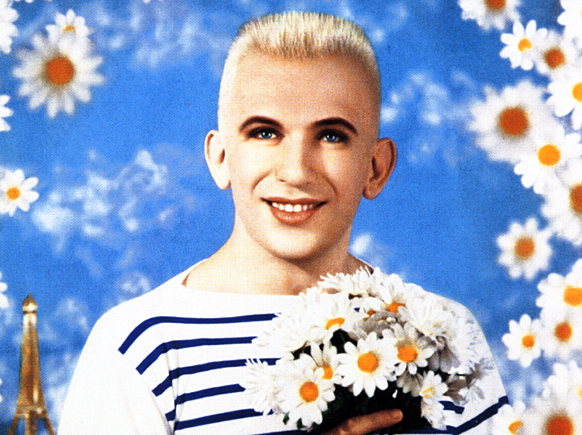

A new Galeries Lafayette poster just appeared, created as usual by the store’s graphiste Jean Paul Goude. It features the aging bad boy Jean-Paul Gaultier, turning his naked chest into a marinière with paint. This is a joke with so many levels that to fully decode it would require a semiotics professor.

The blue-and-white marinière is a French stereotype. Part of the county’s naval uniform since the nineteenth century, it was hijacked for les femmes by Coco Chanel. Some non-French people see wearing the marinière as conformist. (Visitors are frequently surprised by how loyal we can be to stripes and polka dots). But Goude’s poster pokes sly fun at something else. After the World Cup, Nike took charge of the French football team – and one of their first acts was to put the squad into marinières. Those first away shirts were premiered a year ago. Now, Nike is about to field a similar home jersey.

Both have received the same response in public, a mix of controversy and coup de pub.

It involves personalities from sport to haute couture and generates adjectives like “shocking” or “infernal”. Those flames are further fanned by internet polls and newspapers that remind us this is a style worn more by women than men. Fashion as an industry hailed the first shirt right away, giving it an in-house homage at Colette. But its success with the public was limited. Fans like the Sixties designer Jean-Charles de Castelbajac were reduced to citing ancient patrimony. The number of stripes, he noted indignantly, “equals the number of battles won by Napoleon. It is therefore a symbol of victory!”

Much of the public, however, seemed so uneasy Nike stopped marketing the ohé shirt in November. Their new maillot exterièure is almost purged of stripes. Only seven remain on each sleeve.

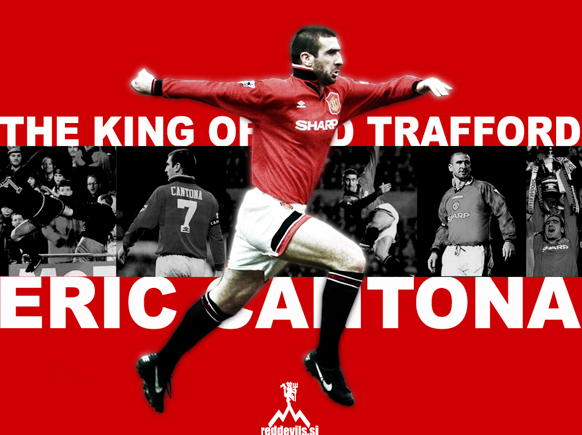

With the new home jersey, Nike has been more cautious. This time, the stripes in Naval blue alternate with a lighter tint, “Pacific”. The PR emphasis is all on advanced technology – how a laser chiselled out each side’s aeration holes, how the fabric is made out of used plastic bottles. There is one fashion first: an upright ‘Mao collar’. This has also been controversial, but some see in it a nod to Eric Cantona. The great Canto always played with his collar flipped up and he has always been one of Nike’s favourite Frenchmen.

Nike’s new collar has another wacky feature. To quote them directly, “Inside the back of the neck, a thin red tape represents the red ribbons worn by the French after the revolution of 1789 celebrating their freedom and their solidarity with the victims of the guillotine”. Say what?

Anyhow, the real subtext of all the controversy is the marinière’s central role in gay iconography. This is something at which Jean-Paul Gaultier is an expert. (Many people think it was he behind Nike’s marinières).

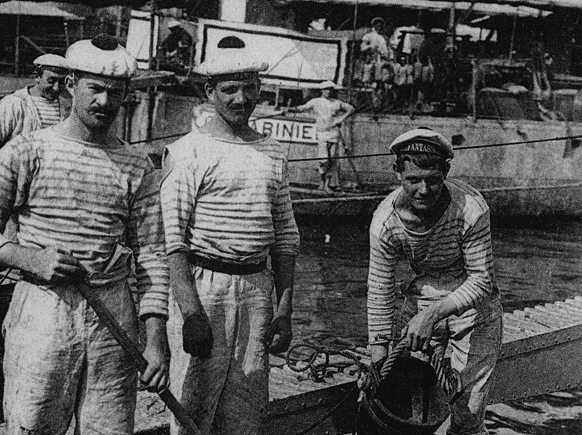

Initially such sailor’s shirts were called simply tricots rayés or “striped jerseys”. As official Navy wear for the lowest of crew members, their stripes were codified by law in 1858. Twenty-one white stripes measure 20 mm, alternating with blue ones of 10 mm. The sleeves are striped with fifteen white bands and fifteen blue ones. Legend says these shirts helped rescue sailors fallen overboard. The item, however, stood for more than just Naval rank. Its wearers were also seen as marginal by “normal” society.

In his fascinating book The Devils Cloth, Michel Pastoreau traces the negative history of stripes in clothing. Associated since the Middle Ages with pariahs – rebel monks, lepers, heretics, clowns, prostitutes, etc – stripes were also worn by the African servants in rich sixteenth-century Venice. Amusingly, the livery of their servitude ended up on the vest of Captain Haddock’s butler, Nestor.

Colonial north America made its revolution with stripes – then the New World’s penal colonies turned them into symbols of guilt and its punishment. However, stripes did indeed enter fashion via the navy. According to research by Aude Le Guennec and Agnès Mirambet-Paris, it was England’s Queen Victoria who put the wheels in motion. From 1846, she dressed her children in the tricots rayés, blouses, pants and pom-pom bonnets of English sailors. This thank-you from their Sovereign proved visionary. For, when increased leisure sent Europe’s rich to the seaside, they went crazy for nautical stripes. From bathing gear to beach huts, they obsessed the Belle Epoque.

The Devil, however, hung on to his cloth. That same iconography which inspired Coco Chanel (and Jeanne Lanvin and, later, Christian Dior) has also always been code for the seamier side of the seaside. Sailor’s bars, deserters, tattoos, prostitution and opium have all contributed to its image. Even the French word for sailor, matelot, comes from the Middle Dutch mattenot, which meant “bed mate”.

From that flip side comes a resonance that would not have amused the Queen. But it’s exactly where Gaultier’s stripes are based, between Jean Genet’s Querelle de Brest – or the Fassbinder film of it loved by JPG – and the French sailor portraits of Pierre et Gilles. As journalist Fabian Cazenave recently noted, certain people speak of audacity, others of pyjamas. It’s not just Goude or Gaultier, you see. You can count on any true Parisian for a double-entendre.

• Les marins font la mode (Gallimard, 2009 for the Musée national de la Marine) will really fill you in. Michel Pastoreau also writes wonderful books about the history of colour and symbols. Check them out.

• Nike Marinière 2011 (directed by Karl Lagerfeld)

• Three things not to miss about Eric Cantona: The Complete Collection DVD the Ken Loach film Looking For Eric and Canto’s fair housing campaign.