A very French Resistance

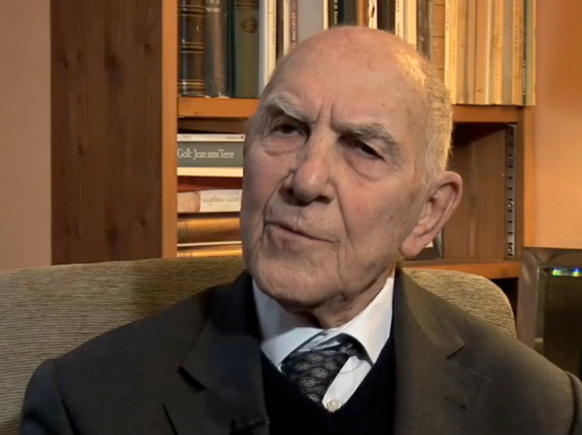

A tall older man (I will learn he is 93) walks toward a seat in this London auditorium. About to see, like all of us, a film about the exiled Free French in the London of World War II. Is he perhaps one of those who appears in the documentary, telling us how that small band found life in those darkest days?

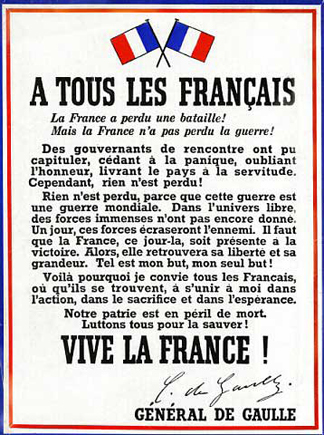

After all, tonight’s screening is a big deal. Seventy years ago this week, Géneral de Gaulle broadcast l’Appel de 18 juin. That “Appeal”, made at the BBC HQ in Portland Place, is usually credited with launching the French Resistance. Tonight launches a week which commemorates the moment, with celebrations in Paris as well as London.

From the crowd’s reaction, however, this could be de Gaulle. People gasp and point, whispering to each other. Him! It’s Stéphane Hessel! Don’t I know his story? Everyone speaks at once. Hessel is, it transpires, one of the ultimate résistants. Born in Berlin – not just a German, either; his father’s family was Jewish. He moved to Paris as a child and his parents knew everyone, everyone from Rilke to Picasso and Marcel Duchamp. Hessel senior even worked alongside Walter Benjamin, translating “Remembrance of Things Past” into German. His mother was a painter and their unconventional marriage later inspired Truffaut’s movie classic Jules et Jim.

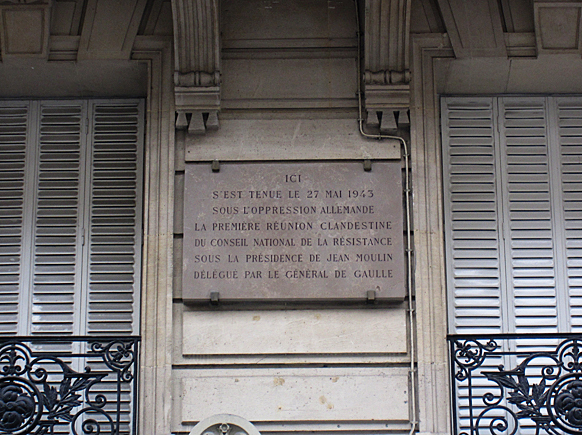

But it was World War II that made Hessel famous. Arrested in France, he escaped to join de Gaulle in London. There, Hessel linked up Britain’s Free French with the Paris résistants. In March of 1944, as part of “Operation Greco”, he was smuggled back to France – where he was betrayed, tortured and sent to Buchenwald to be hanged.

By taking on the identity of a colleague he watched dying of typhus, Hessel managed to survive. But there would be more concentration camps, more death sentences. Escaping en route to Bergen-Belsen, Hessel was saved by Allied troops. After the War, he became a diplomat and a French ambassador and he helped draft the UN’s Declaration of Universal Rights.

His diplomatic assignments included China, Algeria, Geneva and New York and many state honours came his way. Stéphane Hessel! Everyone seems to know his story. Yet none of them, it seems, can believe he’s really here.

Libres Français de Londres, the film, finally begins. Along with other VIP guests, Hessel appears onscreen. The former exiles tell how warmly they were welcomed, how surprised they were by their host city’s generosity (and how unsurprised about its inedible food). They chuckle over their gaffes in English and share winks about les femmes. Afterwards, the directors speak, then Hessel takes the stage. As he starts to answer questions, everyone in the room falls silent.

”We in London,” he says, “had a typical wartime. Bombs were dropping around you all the time. Even France was not so much at war because France was occupied. Which makes me say that to be occupied or even half-occupied is a terrible thing”. He goes on to talk about the Palestinians and the occupation of Iraq.

”When one lives this new twenty-first century,” he concludes, “not yet a good century – although we hope it will become one – one remembers why there is willingness to resist. One understands it, because one was occupied. One understands why we must continue to resist.” The crowd bursts into deafening applause.

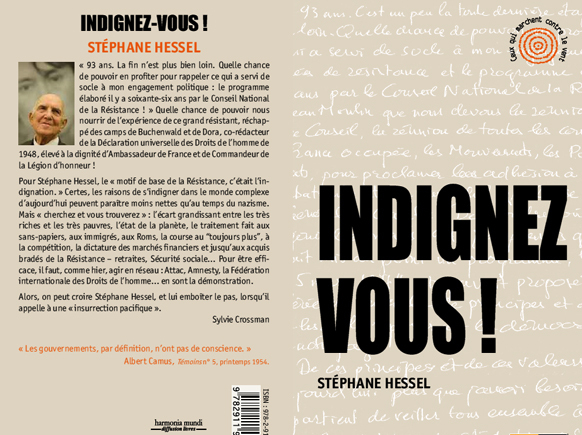

Five months later, with no publicity, a Montpellier press publishes 2,000 copies of an essay by Hessel. Called Indignez-Vous ! (“Get Angry!”), it expands upon the comments heard in London. L’Appel de 18 juin, re-read then with great pomp, concludes with an exhortation: “The flame of French resistance must not and will not be extinguished!” Hessel’s 32-page work proposes re-lighting that flame, by creating a modern network of “citizen résistants”. By early December, it is a best-seller; in less than ten weeks, almost a million copies are purchased.

Hessel makes the headlines. By January, the time has arrived for Sarkozy – as President of the Republic – to present the nation with his televised voeux (New Year’s wishes). Activist web site Mediapart asks Stéphane Hessel to do the same. He does so with both the French and UN flags in front of him.

Soon visible on posters all over Paris, Hessel gives interviews, sees his previous books re-issued, even makes a DVD that is distributed by Le Nouvel Obs (in an issue entitled ”Le Incroyable Hessel”). He is finishing a sequel, too: Engagez-Vous!.

Indignez-Vous ! follows a long French tradition of political pamphlets, from names such as Zola and Balzac (the latter described the format as “sarcasm converted to a cannon ball”). Its indignation targets the gap between the world’s rich and poor as well as the differences in rights they enjoy. More specific reasons for personal engagement are cited: the planet’s health, Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, Sarkozy’s anti-immigrant policies and persistent threats to the French social welfare system.

Hessel discusses one obstacle – personal feelings of powerlessness – that de Gaulle also battled with his wartime broadcasts. Able to evoke his personal role in history, Hessel calls on youth, “to make live again the heritage of the Resistance”, including the social ideas it put forward after the War. These, he emphasises, included the welfare and health systems as well as guarantees for personal dignity, equality…and a free media.

In the essay, Hessel proclaims himself a natural optimist, “one who wants everything desirable to be possible”. He urges his readers to engage with the world’s most difficult problems. But the only possible path, he insists with fervour, is that of pacific resistance: non-violence.

Mainly for his words about the Palestinians and his views on Sarkozy, Hessel’s call has been criticized. But it is proving incredibly resonant, as translations spring up around the world. Indignez-Vous ! has already appeared in four of Spain’s languages (Castilian, Basque, Catalan and Galician) as well as in a Portuguese version prefaced by words from Mario Soares. In Estonia, 30,000 translations were given away. In English (Quartet’s UK translation is called A Time for Outrage), in Korean, Arabic and Hebrew, his words continue to spread. Hessel is now so à la mode (at 93!) some French pundits are now reduced to calling him “naive”.

Yet on behalf of his comrades, the lost as well as the few who survived, Hessel offers today’s youth, “with affection”, a challenge. As one who used poetry as a bulwark against torture, he also adds a special incentive. “To create is to resist,” he promises, “and to resist, to create”.

POSTSCRIPT 2012 In December 2011, when Hessel’s essay was re-launched; “indigné” had become the term for “protester”. (When football star Eric Cantona launched a shock campaign by for Fondation Abbé Pierre, his ads featured a Guignol of the late Abbé himself captioned “Abbe Pierre, Indigné”). At 94, Hessel champions Socialist presidential candidate François Hollande, features in the 2012 Petit Larousse and remains the author of the nation’s 14th best-selling book.

Les vœux de Stéphane Hessel pour 2011 sur Mediapart

envoyé par Mediapart. – L'info internationale vidéo.